The Department of Justice has revised its regulations implementing the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). This rule takes effect on March 15, 2011, clarifies issues that have arisen over the past 20 years, and contains new requirements, including the 2010 Standards for Accessible Design (2010 Standards). This document provides guidance to assist small business owners in understanding how this new regulation applies to them.

Read this to get specific guidance about this topic.

More than 50 million Americans – 18% of our population – have disabilities, and each is a potential customer. People with disabilities are living more independently and participating more actively in their communities. They and their families want to patronize businesses that welcome customers with disabilities. In addition, approximately 71.5 million baby boomers will be over age 65 by the year 2030 and will be demanding products, services, and environments that meet their age-related physical needs. Studies show that once people with disabilities find a business where they can shop or get services in an accessible manner, they become repeat customers.

People with disabilities have too often been excluded from everyday activities: shopping at a corner store, going to a neighborhood restaurant or movie with family and friends, or using the swimming pool at a hotel on the family vacation. The ADA is a Federal civil rights law that prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities and opens doors for full participation in all aspects of everyday life. This publication provides general guidance to help business owners understand how to comply with the Department’s revised ADA regulations and the 2010 Standards, its design standards for accessible buildings. The ADA applies to both the built environment and to policies and procedures that affect how a business provides goods and services to its customers. Using this guidance, a small business owner or manager can ensure that it will not unintentionally exclude people with disabilities and will know when it needs to remove barriers in its existing facilities. If you are planning to build a new facility or alter an existing one, please see New Construction and Alterations for specific guidance on these types of projects. Businesses should consult the revised ADA regulations and the 2010 Standards for more comprehensive information about specific requirements.

Businesses that provide goods or services to the public are called “public accommodations” in the ADA. The ADA establishes requirements for 12 categories of public accommodations, which include stores, restaurants, bars, service establishments, theaters, hotels, recreational facilities, private museums and schools, doctors’ and dentists’ offices, shopping malls, and other businesses. Nearly all types of businesses that serve the public are included in the 12 categories, regardless of the size of the business or the age of their buildings. Businesses covered by the ADA are required to modify their business policies and procedures when necessary to serve customers with disabilities and take steps to communicate effectively with customers with disabilities. The ADA also requires businesses to remove architectural barriers in existing buildings and make sure that newly built or altered facilities are constructed to be accessible to individuals with disabilities. “Grandfather provisions” often found in local building codes do not exempt businesses from their obligations under the ADA.

Commercial facilities, such as office buildings, factories, warehouses, or other facilities that do not provide goods or services directly to the public are only subject to the ADA’s requirements for new construction and alterations.

Businesses need to know two important deadlines for compliance. Starting March 15, 2011, businesses must comply with the ADA’s general nondiscrimination requirements, including provisions related to policies and procedures and effective communication. The deadline for complying with the 2010 Standards, which detail the technical rules for building accessibility, is March 15, 2012. This delay in implementation was provided to allow businesses sufficient time to plan for implementing the new requirements for facilities. In addition, hotels, motels, and inns have until March 15, 2012, to update their reservation policies and systems to make them fully accessible to people with disabilities.

| Date | Compliance |

|---|---|

| March 15, 2011 | General Non-Discrimination Requirements |

| March 15, 2012 | Hotel Reservation Policies |

| March 15, 2012 | 2010 Standards |

Your business, like all others, has formal and informal policies, practices, and procedures that keep it running smoothly. However, sometimes your policies or procedures can inadvertently make it difficult or impossible for a customer with a disability to access your goods and services. That is why the ADA requires businesses to make “reasonable modifications” to their usual ways of doing things when serving people with disabilities. Most modifications involve only minor adjustments in policies. For example, a day care center that has two scheduled snack times must modify this policy to allow a child with diabetes to bring food for an extra snack if necessary. A clothing store must modify a policy of permitting only one person at a time in a dressing room for a person with a disability who is shopping with a companion and needs the companion’s assistance to try on clothes. Anything that would result in a fundamental alteration – a change in the essential nature of your business – is not required. For example, a clothing store is not required to provide dressing assistance for a customer with a disability if this is not a service provided to other customers.

Customers with disabilities may need different types of assistance to access your goods and services. For example, a grocery store clerk is expected to assist a customer using a mobility device by retrieving merchandise from high shelves. A person who is blind may need assistance maneuvering through a store’s aisles. A customer with an intellectual disability may need assistance in reading product labels and instructions. Usually the customer will tell you up front if he or she needs assistance, although some customers may wait to be asked “may I help you?” When only one staff person is on duty, it may or may not be possible for him or her to assist a customer with a disability. The business owner or manager should advise the staff person to assess whether he or she can provide the assistance that is needed without jeopardizing the safe operation of the business.

Often businesses such as stores, restaurants, hotels, or theaters have policies that can exclude people with disabilities. For example, a “no pets” policy may result in staff excluding people with disabilities who use dogs as service animals. A clear policy permitting service animals can help ensure that staff are aware of their obligation to allow access to customers using service animals. Under the ADA’s revised regulations, the definition of “service animal” is limited to a dog that is individually trained to do work or perform tasks for an individual with a disability. The task(s) performed by the dog must be directly related to the person’s disability. For example, many people who are blind or have low vision use dogs to guide and assist them with orientation. Many individuals who are deaf use dogs to alert them to sounds. People with mobility disabilities often use dogs to pull their wheelchairs or retrieve items. People with epilepsy may use a dog to warn them of an imminent seizure, and individuals with psychiatric disabilities may use a dog to remind them to take medication. Service members returning from war with new disabilities are increasingly using service animals to assist them with activities of daily living as they reenter civilian life. Under the ADA, “comfort,” “therapy,” or “emotional support animals” do not meet the definition of a service animal.

Under the ADA, service animals must be harnessed, leashed, or tethered, unless these devices interfere with the service animal’s work or the individual’s disability prevents him from using these devices. Individuals who cannot use such devices must maintain control of the animal through voice, signal, or other effective controls. Businesses may exclude service animals only if 1) the dog is out of control and the handler cannot or does not regain control; or 2) the dog is not housebroken. If a service animal is excluded, the individual must be allowed to enter the business without the service animal.

In situations where it is not apparent that the dog is a service animal, a business may ask only two questions: 1) is the animal required because of a disability; and 2) what work or task has the animal been trained to perform? No other inquiries about an individual’s disability or the dog are permitted. Businesses cannot require proof of certification or medical documentation as a condition for entry.

People with mobility, circulatory, or respiratory disabilities use a variety of devices for mobility. Some use walkers, canes, crutches, or braces while others use manually-operated or power wheelchairs, all of which are primarily designed for use by people with disabilities. Businesses must allow people with disabilities to use these devices in all areas where customers are allowed to go.

Advances in technology have given rise to new power-driven devices that are not necessarily designed for people with disabilities, but are being used by some people with disabilities for mobility. The term “other power-driven mobility devices” is used in the revised ADA regulations to refer to any mobility device powered by batteries, fuel, or other engines, whether or not they are designed primarily for use by individuals with mobility disabilities for the purpose of locomotion. Such devices include Segways®, golf cars, and other devices designed to operate in non-pedestrian areas. Public accommodations must allow individuals who use these devices to enter their premises unless the business can demonstrate that the particular type of device cannot be accommodated because of legitimate safety requirements. Such safety requirements must be based on actual risks, not on speculation or stereotypes about a particular class of devices or how they will be operated by individuals using them.

Businesses must consider these factors in determining whether reasonable modifications can be made to admit other power-driven mobility devices to their premises:

Using these assessment factors, a business may decide that it can allow devices like Segways® in its facilities, but cannot allow the use of golf cars in the same facility. It is likely that many businesses will allow the use of Segways® generally, although some may decide to exclude them during their busiest hours or on particular shopping days when pedestrian traffic is particularly dense. Businesses are encouraged to develop written policies specifying when other power-driven mobility devices will be permitted on their premises and to communicate those policies to the public.

Businesses may ask individuals using an other power-driven mobility device for a credible assurance that the device is required because of a disability. An assurance may include, but does not require, a valid State disability parking placard or other Federal or State-issued proof of disability. A verbal assurance from the individual with a disability that is not contradicted by your observation is also considered a credible assurance. It is not permissible to ask individuals about their disabilities.

Communicating successfully with customers is an essential part of doing business. When dealing with customers who are blind or have low vision, those who are deaf or hard of hearing, or those who have speech disabilities, many business owners and employees are not sure what to do. The ADA requires businesses to take steps necessary to communicate effectively with customers with vision, hearing, and speech disabilities.

Because the nature of communications differs from business to business, the rules allow for flexibility in determining effective communication solutions. What is required to communicate effectively when discussing a mortgage application at a bank or buying an automobile at a car dealership will likely be very different from what is required to communicate effectively in a convenience store. The goal is to find practical solutions for communicating effectively with your customers. For example, if a person who is deaf is looking for a particular book at a bookstore, exchanging written notes with a sales clerk may be effective. Similarly, if that person is going to his or her doctor’s office for a flu shot, exchanging written notes would most likely be effective. However, if the visit’s purpose is to discuss cancer treatment options, effective communication would likely require a sign language or oral interpreter because of the nature, length, and complexity of the conversation. Providing an interpreter guarantees that both parties will understand what is being said. The revised regulations permit the use of new technologies including video remote interpreting (VRI), a service that allows businesses that have video conference equipment to access an interpreter at another location.

It is a business’s responsibility to provide a sign language, oral interpreter, or VRI service unless doing so in a particular situation would result in an undue burden, which means significant difficulty or expense. A business’s overall resources determine (rather than a comparison to the fees paid by the customer needing the interpreter) what constitutes an undue burden. If a specific communications method would be an undue burden, a business must provide an effective alternative if there is one.

Many individuals who are deaf or have other hearing or speech disabilities use either a text telephone (TTY) or text messaging instead of a standard telephone. The ADA established a free telephone relay network to enable these individuals to communicate with businesses and vice versa. When a person who uses such a device calls the relay service by dialing 7-1-1, a communications assistant calls the business and voices the caller’s typed message and then types the business’s response to the caller. Staff who answer the telephone must accept and treat relay calls just like other calls. The communications assistant will explain how the system works if necessary.

The rules are also flexible for communicating effectively with customers who are blind or have low vision. For example, a restaurant can put its menu on an audio cassette or a waiter can read it to a patron. A sales clerk can find items and read their labels. In more complex transactions where a significant amount of printed information is involved, providing alternate formats will be necessary, unless doing so is an undue burden. For example, when a client who is blind visits his real estate agent to negotiate the sale of a house, all relevant documents should be provided in a format he can use, such as on a computer disk or audio cassette. It may be effective to e-mail an electronic version of the documents so the client can use his or her screen-reading technology to read them before making a decision or signing a contract. In this situation, since complex financial information is involved, simply reading the documents to the client will most likely not be effective. Usually a customer will tell you which format he or she needs. If not, it is appropriate to ask.

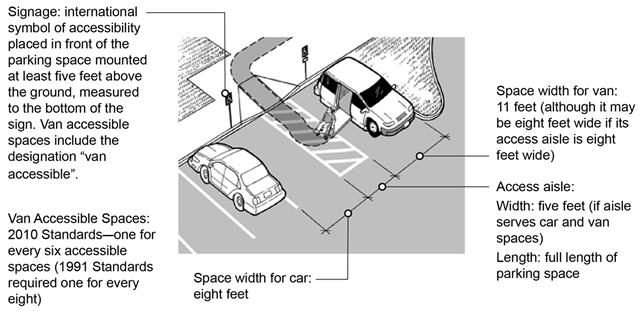

People with disabilities continue to face architectural barriers that limit or make it impossible to access the goods or services offered by businesses. Examples include a parking space with no access aisle to allow deployment of a van’s wheelchair lift, steps at a facility’s entrance or within its serving or selling space, aisles too narrow to accommodate mobility devices, counters that are too high, or restrooms that are simply too small to use with a mobility device.

The ADA strikes a careful balance between increasing access for people with disabilities and recognizing the financial constraints many small businesses face. Its flexible requirements allow businesses confronted with limited financial resources to improve accessibility without excessive expense.

The ADA’s regulations and the ADA Standards for Accessible Design, originally published in 1991, set the standard for what makes a facility accessible. While the updated 2010 Standards retain many of the original provisions in the 1991 Standards, they do contain some significant differences. These standards are the key for determining if a small business’s facilities are accessible under the ADA. However, they are used differently depending on whether a small business is altering an existing building, building a brand new facility, or removing architectural barriers that have existed for years.

If your business facility was built or altered in the past 20 years in compliance with the 1991 Standards, or you removed barriers to specific elements in compliance with those Standards, you do not have to make further modifications to those elements – even if the new standards have different requirements for them – to comply with the 2010 Standards. This provision is applied on an element-by-element basis and is referred to as the “safe harbor.” The following examples illustrate how the safe harbor applies:

The 2010 Standards lower the mounting height for light switches and thermostats from 54 inches to 48 inches. If your light switches are already installed at 54 inches in compliance with the 1991 Standards, you are not required to lower them to 48 inches. The 1991 Standards require one van accessible space for every eight accessible spaces. The 2010 Standards require one van accessible space for every six accessible spaces. If you have complied with the 1991 Standards, you are not required to add additional van accessible spaces to meet the 2010 Standards. The 2010 Standards contain new requirements for the input, numeric, and function keys (e.g. “enter,” “clear,” and “correct”) on automatic teller machine (ATM) keypads. If an existing ATM complies with the 1991 Standards, no further modifications are required to the keypad.

If a business chooses to alter elements that were in compliance with the 1991 Standards, the safe harbor no longer applies to those elements. For example, if you restripe your parking lot, which is considered an alteration, you will now have to meet the ratio of van accessible spaces in the 2010 Standards. Similarly, if you relocate a fixed ATM, which is considered an alteration, you will now have to meet the keypad requirements in the 2010 Standards. The ADA’s definition of an alteration is discussed later in this publication.

The revised ADA rules and the 2010 Standards contain new requirements for elements in existing facilities that were not addressed in the original 1991 Standards. These include recreation facilities such as swimming pools, play areas, exercise machines, miniature golf facilities, and bowling alleys. Because these elements were not included in the 1991 Standards, they are not subject to the safe harbor. Therefore, on or after March 15, 2012, public accommodations must remove architectural barriers to elements subject to the new requirements in the 2010 Standards when it is readily achievable to do so. For example, a hotel must determine whether it is readily achievable to make its swimming pool accessible to people with mobility disabilities by installing a lift or a ramp as specified in the 2010 Standards.

New Requirements in the 2010 Standards Not Subject to the Safe HarborThe ADA requires that small businesses remove architectural barriers in existing facilities when it is “readily achievable” to do so. Readily achievable means “easily accomplishable without much difficulty or expense.” This requirement is based on the size and resources of a business. So, businesses with more resources are expected to remove more barriers than businesses with fewer resources.

Readily achievable barrier removal may include providing an accessible route from a parking lot to the business’s entrance, installing an entrance ramp, widening a doorway, installing accessible door hardware, repositioning shelves, or moving tables, chairs, display racks, vending machines, or other furniture. When removing barriers, businesses are required to comply with the Standards to the extent possible. For example, where there is not enough space to install a ramp with a slope that complies with the Standards, a business may install a ramp with a slightly steeper slope. However, any deviation from the Standards must not pose a significant safety risk.

Determining what is readily achievable will vary from business to business and sometimes from one year to the next. Changing economic conditions can be taken into consideration in determining what is readily achievable. Economic downturns may force many public accommodations to postpone removing some barriers. The barrier removal obligation is a continuing one and it is expected that a business will move forward with its barrier removal efforts when it rebounds from such downturns. For example, if a restaurant identified barriers under the 1991 Standards but did not remove them because it could not afford the cost, the restaurant has a continuing obligation to remove these barriers when it has the financial resources to do so.

Businesses removing barriers before March 15, 2012, have the choice of using either the 1991 Standards or the 2010 Standards. You must use only one standard for removing barriers in an entire facility. For example, you cannot choose the 1991 Standards for accessible routes and the 2010 Standards for restrooms. (See, ADA 2010 Revised Requirements: Effective Date / Compliance Date at https://archive.ada.gov/revised_effective_dates-2010.htm. Remember that if an element complies with the 1991 Standards, a business is not required to make any changes to that element until such time as the business decides to alter that element.

| Compliance Date | Applicable Standard |

|---|---|

| Until March 15, 2012 | 1991 Standards or 2010 Standards |

| On or after March 15, 2012 | 2010 Standards |

Understanding how customers arrive at and move through your business will go a long way in identifying existing barriers and setting priorities for their removal. Do people arrive on foot, by car, or by public transportation? Do you provide parking? How do customers enter and move about your business? The ADA regulations recommend the following priorities for barrier removal:

Businesses should not wait until March 15, 2012 to identify existing barriers, but should begin now to evaluate their facilities and develop priorities for removing barriers. Businesses are also encouraged to consult with people with disabilities in their communities to identify barriers and establish priorities for removing them. A thorough evaluation and barrier removal plan, developed in consultation with the disability community, can save time and resources.

In some instances, especially in older buildings, it may not be readily achievable to remove some architectural barriers. For example, a restaurant with several steps leading to its entrance may determine that it cannot afford to install a ramp or a lift. In this situation, the restaurant must provide its services in another way if that is readily achievable, such as providing takeout service. Businesses should train staff on these alternatives and publicize them so customers with disabilities will know of their availability and how to access them.

If your business provides parking for the public, but there are no accessible spaces, you will lose potential customers. You must provide accessible parking spaces for cars and vans if it is readily achievable to do so. The chart below indicates the number of accessible spaces required by the 2010 Standards. One of every six spaces must be van accessible.

| Total Number of Parking Spaces Provided in Parking Facility | Minimum Number of Required Accessible Parking Spaces |

|---|---|

| 1 to 25 | 1 |

| 26 to 50 | 2 |

| 51 to 75 | 3 |

| 76 to 100 | 4 |

| 101 to 150 | 5 |

| 151 to 200 | 6 |

| 201 to 300 | 7 |

| 301 to 400 | 8 |

| 401 to 500 | 9 |

| 501 to 1000 | 2 percent of total |

| 1001 and over | 20, plus 1 for each 100, or fraction thereof, over 1000 |

Small businesses with very limited parking (four or fewer spaces) must have one accessible parking space. However, no signage is required.

An accessible parking space must have an access aisle, which allows a person using a wheelchair or other mobility device to get in and out of the car or van.

One small step at an entrance can make it impossible for individuals using wheelchairs, walkers, canes, or other mobility devices to do business with you. Removing this barrier may be accomplished in a number of ways, such as installing a ramp or a lift or regrading the walkway to provide an accessible route. If the main entrance cannot be made accessible, an alternate accessible entrance can be used. If you have several entrances and only one is accessible, a sign should be posted at the inaccessible entrances directing individuals to the accessible entrance. This entrance must be open whenever other public entrances are open.

The path a person with a disability takes to enter and move through your business is called an “accessible route.” This route, which must be at least three feet wide, must remain accessible and not be blocked by items such as vending or ice machines, newspaper dispensers, furniture, filing cabinets, display racks, or potted plants. Similarly, accessible toilet stalls, dressing rooms, or counters at a cash register must not be cluttered with merchandise or supplies.

Temporary access interruptions for maintenance, repair, or operational activities are permitted, but must be remedied as soon as possible and may not extend beyond a reasonable period of time. Businesses must be prepared to retrieve merchandise for customers during these interruptions. For example, if an aisle is temporarily blocked because shelves are being restocked, staff must be available to assist a customer with a disability who is unable to maneuver through that aisle. In addition, if an accessible feature such as an elevator breaks down, businesses must ensure that repairs are made promptly and that improper or inadequate maintenance does not cause repeated failures. Businesses must also ensure that no new barriers are created that impede access by customers with disabilities. For example, routinely storing a garbage bin or piling snow in accessible parking spaces makes them unusable and inaccessible to customers with mobility disabilities.

The obligation to remove barriers also applies to merchandise shelves, sales and service counters, and check-out aisles. Shelves and counters must be on an accessible route with enough space to allow customers using mobility devices to access merchandise. However, shelves may be of any height since they are not subject to the ADA’s reach range requirements. Where barriers prevent access to these areas, they must be removed if readily achievable. However, businesses are not required to take any steps that would result in a significant loss of selling space. At least one check-out aisle must be usable by people with mobility disabilities, though more are required in larger stores. When it is not readily achievable to make a sales or service counter accessible, businesses should provide a folding shelf or a nearby accessible counter. If these changes are not readily achievable, businesses may provide a clip board or lap board until more permanent changes can be made.

People with disabilities need to access tables, food service lines, and condiment and beverage bars in restaurants, bars, or other establishments where food or drinks are sold. There must be an accessible route to all dining areas, including raised or sunken dining areas and outdoor dining areas, as well as to food service lines, service counters, and public restrooms. In a dining area, remember to arrange tables far enough apart so a person using a wheelchair can maneuver between the tables when patrons are sitting at them. Some accessible tables must be provided and must be dispersed throughout the dining area rather than clustered in a single location.

Where barriers prevent access to a raised, sunken, or outdoor dining area, they must be removed if readily achievable. If it is not readily achievable to construct an accessible route to these areas and distinct services (e.g., special menu items or different prices) are available in these areas, the restaurant must make these services available at the same price in the dining areas that are on an accessible route. In restaurants or bars with only standing tables, some accessible dining tables must be provided.

The ADA requires that all new facilities built by public accommodations, including small businesses, must be accessible to and usable by people with disabilities. The 2010 Standards lay out accessibility design requirements for newly constructed and altered public accommodations and commercial facilities. Certain dates in the construction process determine which ADA standards – the 1991 Standards or the 2010 Standards – must be used.

If the last or final building permit application for a new construction or alterations project is certified before March 15, 2012, businesses may comply with either the 1991 or the 2010 Standards. In jurisdictions where certification of permit applications is not required, businesses can also choose between the 1991 or 2010 Standards if their jurisdiction receives their permit application by March 15, 2012. Businesses should refer to their local permitting process. Where no permits are required, businesses may comply with either the 1991 or 2010 Standards if physical construction starts before March 15, 2012. Start of physical construction or alterations does not mean the date of ceremonial ground breaking or the day demolition of an existing structure commences. In this situation, if physical construction starts after March 15, 2012, the business must use the 2010 Standards.

When a small business undertakes an alteration to any of its facilities, it must, to the maximum extent feasible, make the alteration accessible. An alteration is defined as remodeling, renovating, rehabilitating, reconstructing, changing or rearranging structural parts or elements, changing or rearranging plan configuration of walls and full-height partitions, or making other changes that affect (or could affect) the usability of the facility.

Examples include restriping a parking lot, moving walls, moving a fixed ATM to another location, installing a new sales counter or display shelves, changing a doorway entrance, replacing fixtures, flooring or carpeting. Normal maintenance, such as reroofing, painting, or wallpapering, is not an alteration.

2010 ADA Standards BasicsChapter 1: Application and Administration Contains important introductory and interpretive information, including definitions for key terms used in the 2010 Standards.

Chapter 2: Scoping Sets forth what elements and how many of them must be accessible. Scoping covers newly constructed facilities and altered portions of existing facilities.

Note: The 2010 Standards do not address barrier removal. The revised regulations, however, require that barrier removal must comply with the 2010 Standards to the extent it is readily achievable.

Chapters 3 – 10: Design and Technical Requirements Provides design and technical specifications for elements, spaces, buildings, and facilities.

Common Provisions for Small BusinessAccessible Route Section 206 and Chapter 4

Parking Spaces Sections 208 and 502 specifically address parking spaces. The provisions regarding accessible route (section 206 and chapter 4), signs (section 216), and, where applicable, valet parking (section 209) also apply.

Passenger Loading Zones Sections 209 and 503

Sales and Service Sections 227 and 904 specifically cover sales and service areas, such as check-out aisles and sales and service counters. Section 226.1, exempts sales and service counters from the technical requirements of 902 (dining surfaces and work surfaces).

Dining Surfaces Sections 226 and 902 specifically address fixed dining surfaces. The provisions regarding accessible routes in section 206.2.5 (Restaurants and Cafeterias) and 226.2 (Dispersion) also apply to dining surfaces.

Dressing, Fitting, and Locker Rooms Sections 222 and 803 cover dressing, fitting, and locker rooms. The provisions on doors in sections 206.5 and 404 usually apply.

Being proactive is the best way to ensure ADA compliance. Evaluate access at your facility, train your staff on the ADA’s requirements, think about the ADA when planning an alteration or construction of a new facility, and, most importantly, use the free information resources available whenever you have a question.

The revised ADA regulations give businesses 18 months (until March 15, 2012) before they must comply with the 2010 Standards. The purpose of this phase-in period is to provide businesses sufficient time to plan and comply. Businesses are strongly encouraged to assess their facilities now to determine what architectural barriers exist. Until March 15, 2012, you have the choice of using the 1991 Standards or the 2010 Standards to remove architectural barriers, alter, or construct a new facility. Businesses that use the 1991 Standards during this phase-in period can take advantage of the safe harbor provision. Beginning March 15, 2012, only the 2010 Standards can be used.

A critical and often overlooked component of ensuring success is comprehensive and ongoing staff training. You may have established good policies, but if front line staff are not aware of them or do not know how to implement them, problems can arise. Businesses of all sizes should educate staff about the ADA’s requirements. Staff need to understand the requirements on modifying policies and practices, communicating with and assisting customers, and accepting calls placed through the relay system. Many local disability organizations, including Centers for Independent Living, conduct ADA trainings in their communities. The Department of Justice or the ADA National Network can provide local contact information for these organizations.

To assist small businesses to comply with the ADA, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Code includes a Disabled Access Credit (Section 44) for businesses with 30 or fewer full-time employees or with total revenues of $1 million or less in the previous tax year. Eligible expenses may include the cost of undertaking barrier removal and alterations to improve accessibility, providing sign-language interpreters, or making material available in accessible formats such as Braille, audiotape, or large print.

Section 190 of the IRS Code provides a tax deduction for businesses of all sizes for costs incurred in removing architectural barriers in existing facilities or alterations. The maximum deduction is $15,000 per year.

U.S. Department of Justice

For more information about the revised ADA regulations and 2010 ADA Standards, please visit the Department of Justice’s ADA Website or call our toll-free number.

ADA Information Line 800-514-0301 (Voice) and 1-833-610-1264 (TTY) M-W, F 9:30 a.m. – 12:00 p.m. and 3:00 p.m. - 5:30 p.m., Th 2:30 p.m. – 5:30 p.m. (Eastern Time) to speak with an ADA Specialist. Calls are confidential.

“Reaching Out to Customers with Disabilities” explains the ADA’s requirements for businesses in a short 10-lesson online course.

ADA National Network (DBTAC)

Ten regional centers are funded by the U.S. Department of Education to provide ADA technical assistance to businesses, States and localities, and persons with disabilities. One toll-free number connects you to the center in your region:

Access Board

For technical assistance on the ADA/ABA Accessibilty Guidelines:

Internal Revenue Service

For information on the Disabled Access Tax Credit (Form 8826) and the Section 190 tax deduction (Publication 535 Business Expenses):

800-829-3676 (Voice) or 800-829-4059 (TTY) http://www.irs.gov/

This publication is available in alternate formats for persons with disabilities.

This document has been developed for small businesses in accordance with the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Flexibility Act of 1996.

The Americans with Disabilities Act authorizes the Department of Justice (the Department) to provide technical assistance to individuals and entities that have rights or responsibilities under the Act. This document provides informal guidance to assist you in understanding the ADA and the Department’s regulations.

This guidance document is not intended to be a final agency action, has no legally binding effect, and may be rescinded or modified in the Department’s complete discretion, in accordance with applicable laws. The Department’s guidance documents, including this guidance, do not establish legally enforceable responsibilities beyond what is required by the terms of the applicable statutes, regulations, or binding judicial precedent.

Duplication of this document is encouraged.

Originally issued: March 01, 2011

Last updated: February 28, 2020